To know a truth well, one must have fought it out

… Doing it Right …

Inquire ~ inform ~ integrity

The Goal of this Website

The goal of the Website is to provide clinicians useful, evidence-based information regarding sepsis and its management. We will not perpetuate the mistruths and unscientific information generated by the Early Goal Directed study [1]and propagated by the Surviving Sepsis Campaign [2-5]and other affiliated organizations. This website will be devoid of commercial, financial and other conflicts of interest.

Our goal is to:

Inform, generate Inquiry with open discussion and to do this with Integrity and honesty.

- What is Sepsis!

- DefiningSepsis

- How common is Sepsis!

- Who is at Risk?

- Why is this Important!

Sepsis is a life-threatening condition that arises when the body's response to infection causes injury to its own tissues and organs.Sepsis is best described as infection complicated by organ dysfunction.Sepsis is caused by an immune response triggered by an infection.

William Osler has commented that “Except for a few occasions patients’ appear to die fromthe body’s response to infection rather than from it”[6]

The most common cause of sepsis is pneumonia, followed by abdominal/pelvic infections and “uro-sepsis.” Most commonly, the infection is caused by a bacteria, sometimes a fungus and rarely a virus.

The word “sepsis” is derived from the ancient Greek word for rotten flesh and putrefaction. Since then, a wide variety of definitions have been applied to sepsis, including sepsis syndrome, severe sepsis, bacteremia, septicemia and, septic shock. In 1991, the American College of Chest Physicians (ACCP) and the Society of Critical Care Medicine (SCCM) developed a new set of terms and definitions to define sepsis in a more “precise manner.”[8] These definitions took into account the findings that sepsis may result from a multitude of infectious agents and microbial mediators and may not be associated with detectable bloodstream infection. The term “systemic inflammatory response syndrome” (SIRS) was coined to describe the common systemic response to a wide variety of insults. Four SIRS criteria were defined, namely:

- Tachycardia (heart rate > 90 beats/min)

- Tachypnea (respiratory rate > 20 breaths/min)

- Fever or hypothermia (temperature > 38oC or less than 36oC)

- Leukocytosis, leukopenia, or bandemia (WBC > 1200/mm3, < 4000/mm3 or bandemia ≥ 10%).

Patients who met two or more of these criteria fulfilled the definition of SIRS. When SIRS was the result of a suspected or confirmed infectious process, patients were defined as having “sepsis”. Severe sepsis was defined as sepsis plus organ dysfunction. Septic shock was a subset of severe sepsis and was defined as “sepsis-induced hypotension persisting despite adequate fluid resuscitation”. However, it became evident that the use of the SIRS criteria to define sepsis was problematic, as it lacked both sensitivity and specificity. In order to “improve” on these definitions, updated definitions for sepsis and septic shock were released in 2016 by the Third International Consensus Taskforce (Sepsis-3).[12-14] Sepsis was defined as life-threatening organ dysfunction caused by a dysregulated host response to infection. For clinical operationalization, organ dysfunction was defined as an increase in the Sequential Sepsis Organ Assessment (SOFA) score of 2 or more points for patients in the ICU. A new bedside score termed quickSOFA (qSOFA) was developed to describe organ dysfunction in non-ICU patients. Patients required at least 2 of the following qSOFA criteria to be diagnosed as having sepsis:

- Respiratory rate of 22/min or greater

- Altered mentation

- A systolic blood pressure of 100 mmHg or less.

Septic shock was defined as a subset of sepsis with “profound circulatory, cellular and metabolic abnormalities”. Patients with septic shock are identified by the requirement for vasopressors to maintain a mean arterial pressure of 65 mmHg or greater and a serum lactate greater than 2 mmol/L in the “absence of hypovolemia”. With the new definitions, the “SIRS criteria” are no longer used to screen for or diagnose sepsis and the term “severe sepsis” was removed.

While the qSOFA score may predict mortality with greater accuracy than the SIRS criteria, for the clinician at the bedside it appears that qSOFA and the new SEPS-3 definitions have very little (if any) utility. While not perfect the SIRS construct remains useful for the early identification of sepsis. However, it is important to emphasize that no screening tool or checklist trumps sound clinical judgement.

The precise prevalence of sepsis is difficult to determine. It has been estimated that over 300 million patients develop pneumonia across the globe each year.[7]A conservative estimate suggests that that Global annual burden of sepsis is approximately 20 million cases.[8]The incidence of severe sepsis in the United States is estimated to be about 300 cases per 100,000 population. [9-11]Data from 2004-2009 demonstrates a 13% average annual increase for the incidence of severe sepsis.[9]

Sepsis is among the most common reasons for admission to ICU’s throughout the world. An epidemiologic study in European ICU’s demonstrated a prevalence of 37% for sepsis and 30% for severe sepsis.[12]

Sepsis is predominantly a disease of the elderly, with the majority of cases of sepsis occurring in patients over the age of 65 years. [13]With the ageing of the population this finding largely explains the increasing incidence of sepsis in Western Nations. Sepsis is reported to be more common in men and among nonwhite persons.[10] Surgical patients account for nearly one third of sepsis cases in the US.

Why is this Important!

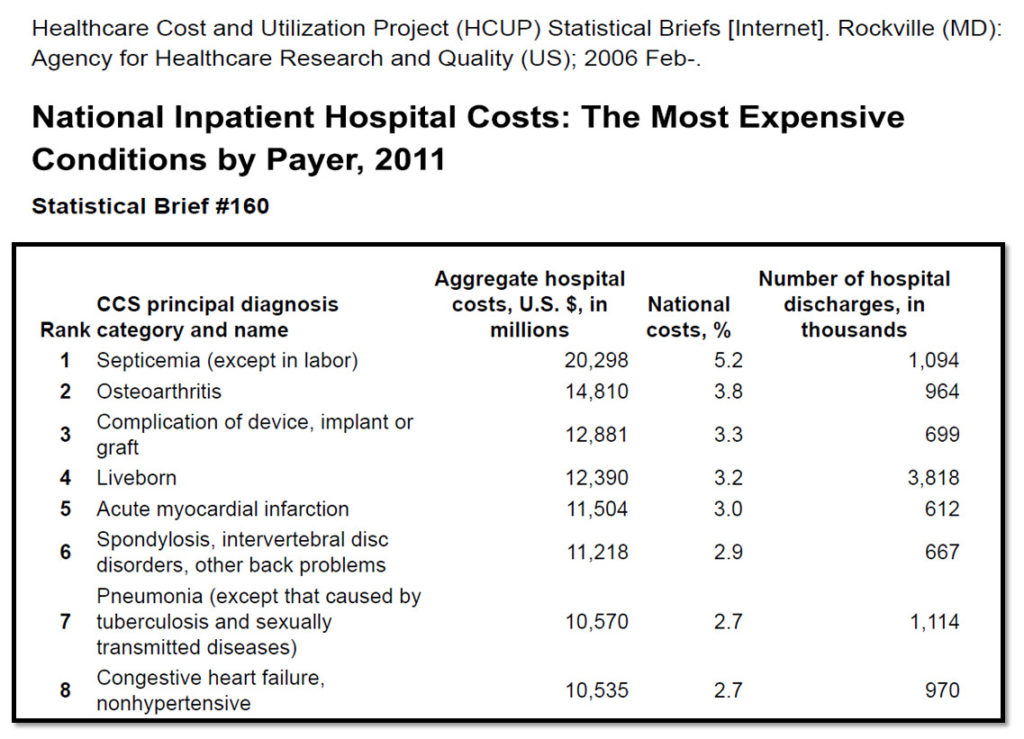

As is indicated in the table below, the most current data in the USA indicates that sepsis is the most costly disease amongst hospitalized patients and the leading cause of death.[14]With more timely diagnosis and improvement in supportive care the 28-day mortality from sepsis in high income countries has declined to about 25%, however, the mortality from septic shock remains as high as 45%. [9,15]However, the mortality from sepsis and septic shock in low income countries is reported to be as high as 60%.[16-18]

Sepsis survivors are at an increased risk death, major adverse cardiovascular events, ischemic stroke, hemorrhagic stroke, myocardial infarction, recurrent sepsis and heart failure compared to population controls. [19,20] In addition, sepsis survivors incur long-term consequences, including developing new physical, psychiatric, and cognitive deficits. These deficits often limit their mobility and ability to perform day-to-day activities and impair quality of life.[20,21]Yende et al demonstrated that among patients who lived independently prior to severe sepsis, at six months’ post hospital discharge one third had died and of those who survived, a further one third had not returned to independent living.[22]

References

- Rivers E, Nguyen B, Havstad S et al. Early goal-directed therapy in the treatment of severe sepsis and septic shock. N Engl J Med 2001; 345:1368-77.

- Dellinger RP, Carlet JM, Masur H et al. Surviving Sepsis Campaign guidelines for management of severe sepsis and septic shock. Crit Care Med 2004; 32:858-73.

- Dellinger RP, Levy MM, Carlet JM et al. Surviving sepsis Campaign: International guidelines for management of severe sepsis and septic shock: 2008. Crit Care Med 2008; 36:296-327.

- Dellinger RP, Levy MM, Rhodes A et al. Surviving Sepsis Campaign: International Guielines for Management of Severe Sepsis and Septic Shock: 2012. Crit Care Med 2013; 41:580-637.

- Rhodes A, Evans L, Alhazzani W et al. Surviving Sepsis Campaign: International Guidelines for Management of Sepsis and Septic Shock:2016. Crit Care Med 2017; 45:486-552.

- Osler W. Pneumonias and Pneumococcic Infections. The Principles and Practice of Medicine. 8th ed. New York: D.Appleton & Co.; 1918: 74-108.

- Global, regional, and national incidence, prevalence, and years lived with disability for 310 diseases and injuries, 1990-2015: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2015. Lancet 2016; 388:1545-602.

- Adhikari NK, Fowler RA, Bhagwanjee S et al. Critical care and the global burden of critical illness in adults. Lancet 2010; 376:1339-46.

- Gaieski DF, Edwards JM, Kallan MJ et al. Benchmarking the incidence and mortality of severe sepsis in the United States. Crit Care Med 2013; 41:1167-74.

- Martin GS, Mannino DM, Eaton S et al. The epidemiology of sepsis in the United States from 1979 through 2000. N Engl J Med 2003; 348:1546-54.

- Angus DC, Linde-Zwirble WT, Lidicker J et al. Epidemiology of severe sepsis in the United States:Analysis of incidence, outcome and associated costs of care. Crit Care Med 2001; 29:1303-10.

- Vincent JL, Sakr Y, Sprung CL et al. Sepsis in European intensive care units: results of the SOAP study. Crit Care Med 2006; 34:344-53.

- Kumar G, Kumar N, Taneja A et al. Nationwide trends of severe sepsis in the 21st Century (2000-2007). Chest 2011; 140:1223-31.

- Torio, C. M. and Andrews, R. M. National Inpatient Hospital Costs: The Most expensive Conditions by Payer, 2011:Statistical Brief #160. Healthcare Costs and Utilization Project (HCUP) Statistical Briefs. 2013. Rockville, MD, Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. 8-1-2013.

- Kaukonen KM, Bailey M, Suzuki S et al. Mortality related to severe sepsis and septic shock among critically ill patients in Australia and New Zealand, 2000-2012. JAMA 2014; 311:1308-16.

- Silva E, de Almeida Pedro M, Beltrami Sogayar AC et al. Brazilian Sepsis Epidemiological Study (BASES study). Crit Care 2004; 8:R251-R260.

- Sales JA, David CM, Hatum R et al. Sepse Brasil: Estudo Epidemiologico da Sepse em Unidades de Terapia Intensiva Brasileiras. An epidemiological study of sepsis in Intensive Care Units. Sepsis Brazil Study. Rev Bras Ter Int 2006; 18:9-17.

- The10 leading causes of death by country income group 2012. WHO factsheets. http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs310/en/index1.html . 2015. World Health Organization. 5-24-2016.

- Ou SM, Chu H, Chao PW et al. Long-term mortality and major adverse cardiovascular events in sepsis survivors. A Nationwide population-based study. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2016; 194:209-17.

- Winters BD, Eberlein M, Leung J et al. Long-term mortality and quality of life in sepsis: a systematic review. Crit Care Med 2010; 38:1276-83.

- Karlsson S, Ruokonen E, Varpula T et al. Long-term outcome and quality-adjusted life years after severe sepsis. Crit Care Med 2009; 37:1268-74.

- Yende S, Austin S, Rhodes A et al. Long-term qualityof life among survivors of severe sepsis: Analyses of two international trials. Crit Care Med 2016; 44:1461-67.